Life Expectancy vs. Income in the United States

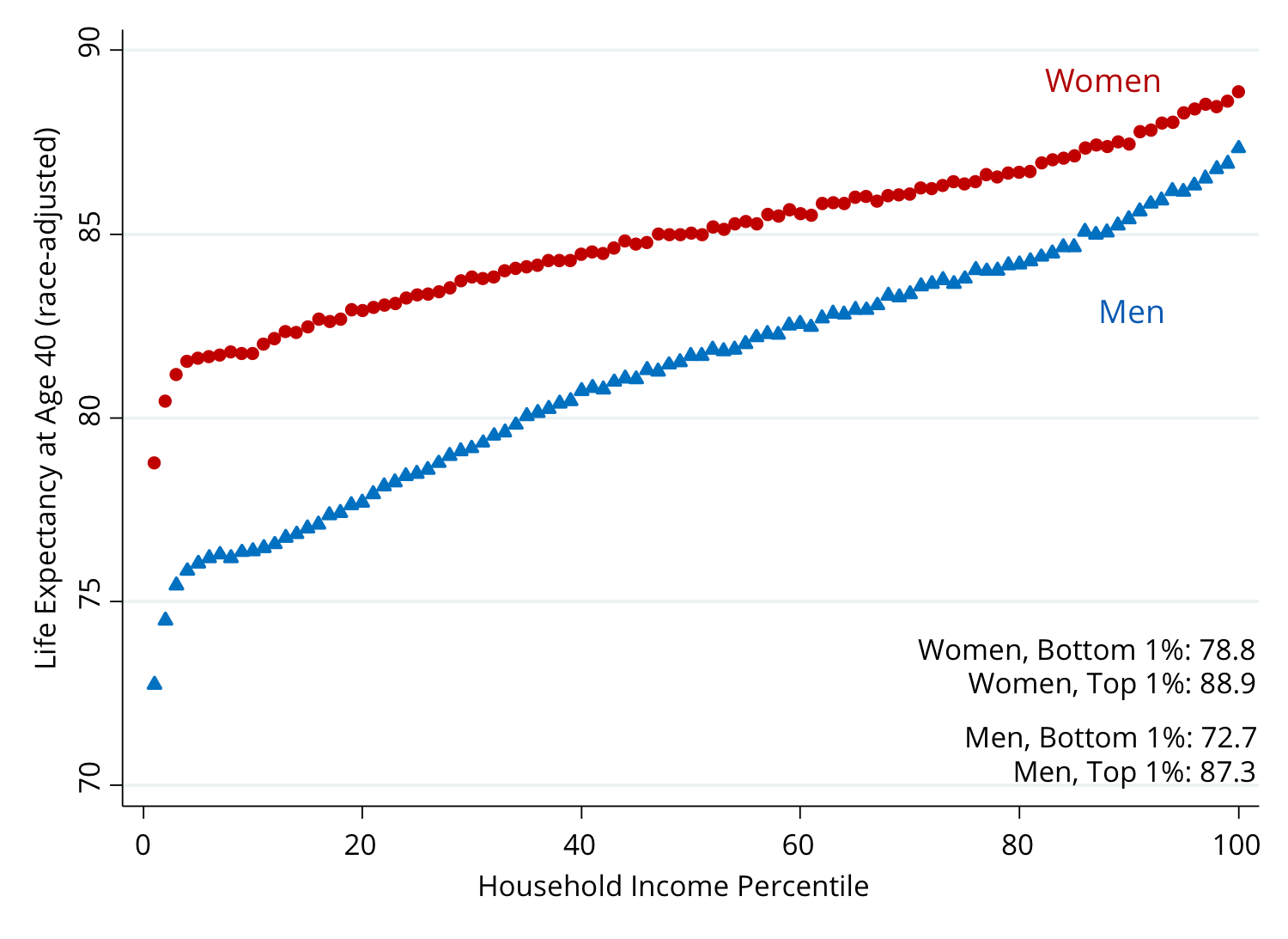

The richest American men live 15 years longer than the poorest men, while the richest American women live 10 years longer than the poorest women.

How can we reduce disparities in health?

The Health Inequality Project uses big data to measure differences in life expectancy by income across areas and identify strategies to improve health outcomes for low-income Americans. To learn more, see this short videoshort video, our executive summary, or our paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The richest American men live 15 years longer than the poorest men, while the richest American women live 10 years longer than the poorest women.

The gaps between the rich and the poor are growing rapidly over time. From 2001-2014, the richest Americans gained approximately 3 years in longevity, but the poorest Americans experienced no gains.

The gains in lifespan for the rich are the equivalent of curing cancer; the CDC estimates that eliminating all cancer deaths would increase average lifespans by 3.2 years.

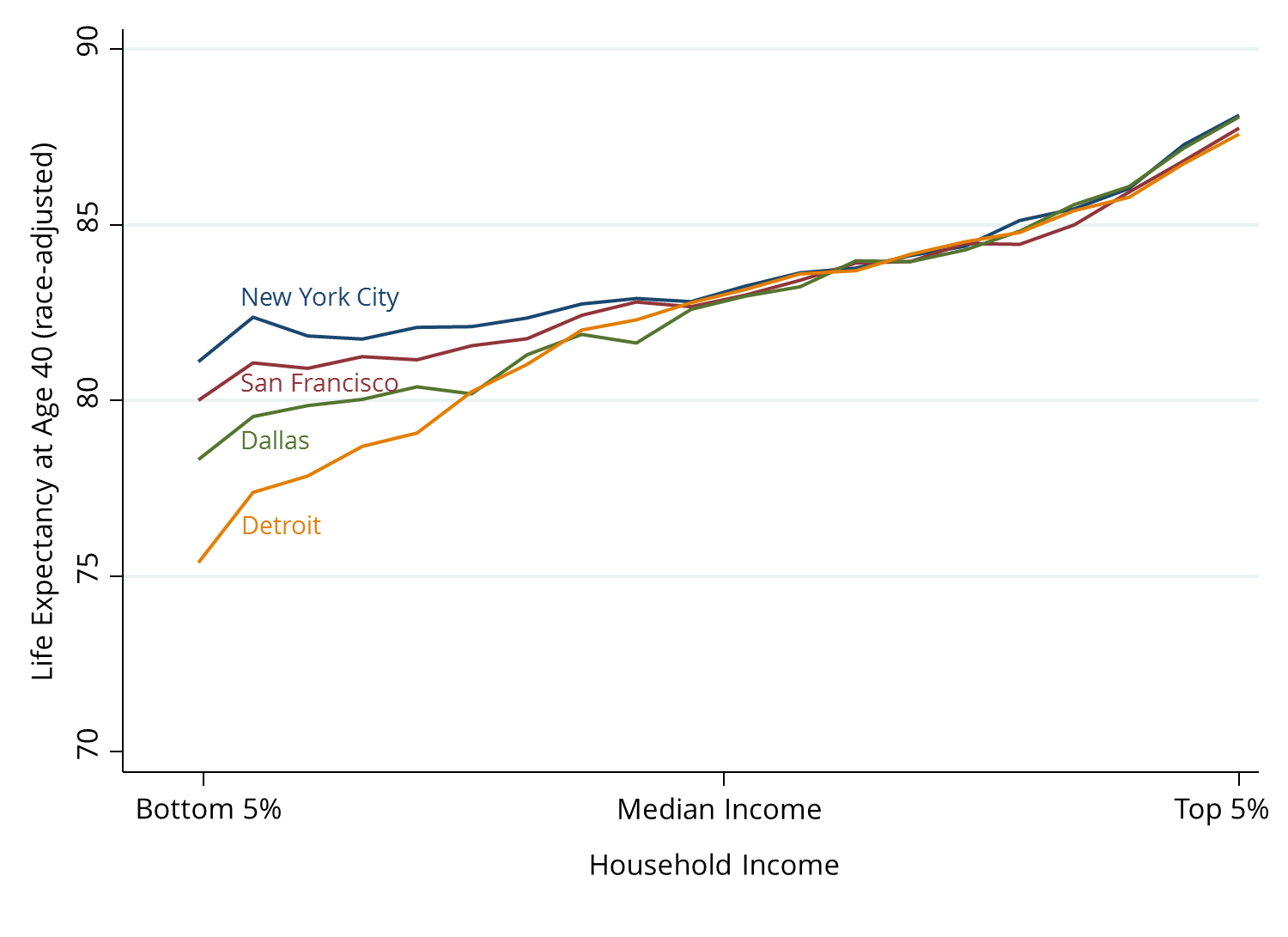

Life expectancy varies substantially across cities, especially for low-income people. For the poorest Americans, life expectancies are 6 years higher in New York than in Detroit. For the richest Americans, the difference is less than 1 year.

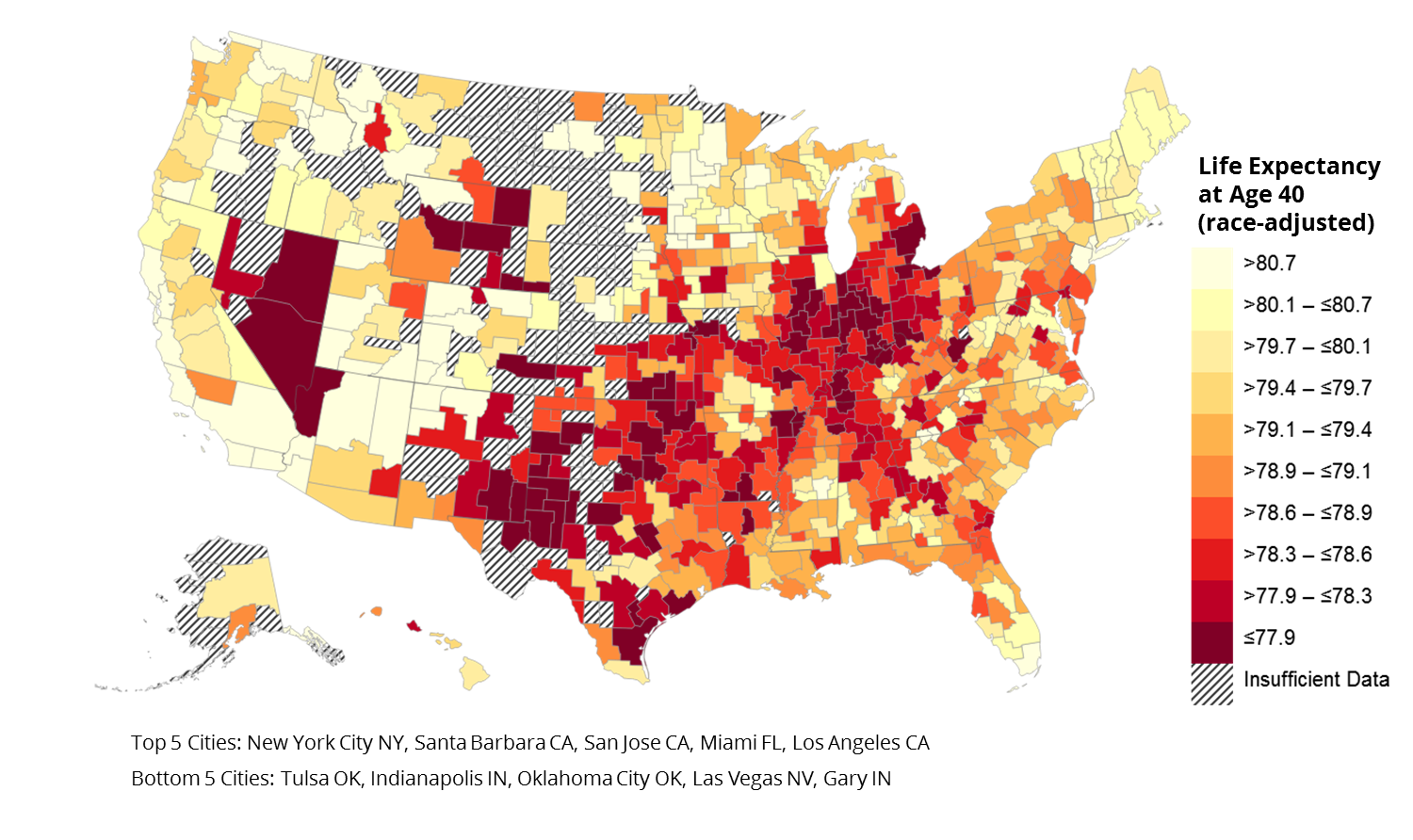

For low-income people, life expectancy is highest in California, New York, and Vermont. It is lowest in Nevada. The next 8 states with the lowest life expectancies form a belt connecting Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Kansas.

Much of the variation in life expectancy across areas is explained by differences in health behaviors, such as smoking and exercise. Differences in life expectancy among the poor are not strongly associated with differences in access to health care or levels of income inequality. Instead, the poor live longest in affluent cities with highly educated populations and high levels of local government expenditures, such as New York and San Francisco.

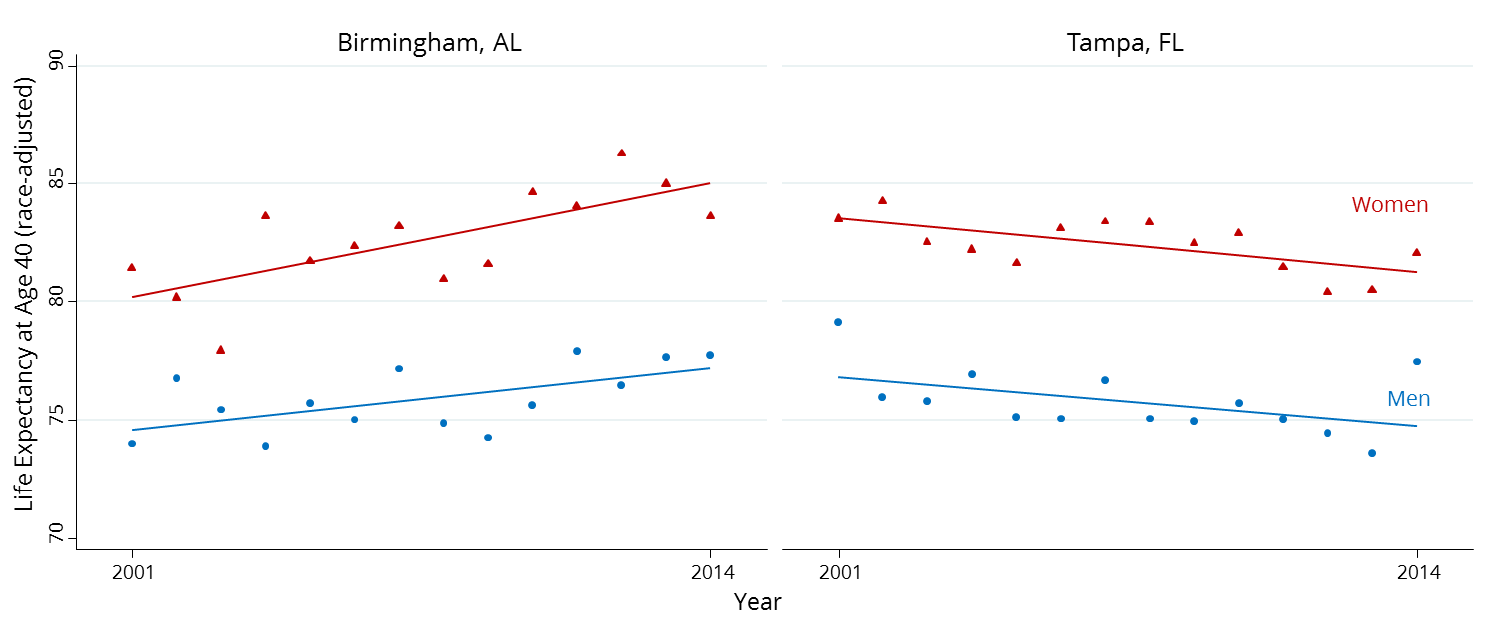

Changes in life expectancy also differ sharply across areas. In Birmingham, AL the poor gained 3.7 years in life expectancy from 2001-2014, about the same as the average increase in life expectancy for the richest Americans. In Tampa, FL the poor lost 2.2 years of life expectancy over the same period.

Our findings show that inequality in life expectancy is not inevitable. There are cities throughout America — from New York to San Francisco to Birmingham, AL — where gaps in life expectancy are relatively small or are narrowing over time.

Replicating these successes more broadly will likely require targeted local efforts to improve health behaviors among low-income people in local communities. The local data on life expectancy by income group constructed in this project offer a lens to monitor local progress and identify promising solutions to reduce disparities in health.